At the sight of the Latin legions, not only did all of the basest class, the foolish and the unwarlike, groan, cry out, and beat their breasts in their fear, not knowing what else to do; but even the zealous adherents of the Emperor, mindful of that Friday on which the seizure of the city had formerly taken place, feared the present day lest vengeance should fall violently upon them for the deeds committed at that time. However, all who had any acquaintance with military practice and skill poured in at the regal palace, each man coming by himself.

But the Emperor neither armed his sides with breastplate of scale-armor, his left hand with a shield, his right with a spear, nor girded himself about with a sword; but, clothed in royal raiment, he seated himself upon the imperial throne, as though secure. Thus, on the one hand, he reassured all, injecting courage into their hearts by his happy look, and, on the other, he discussed with his advisers and military leaders plans for coming events. First of all, he absolutely refused to have any armed band led outside of the walls against the Latins, this for a twofold reason: First, because this was the most sacred of days, for it was Friday of the greatest, of Holy, Week, when the Saviour had undergone ignominious death for all. In the second place, he refused to engage in civil war between Christians.

Therefore, by means of frequent messengers to the Latins he wished to bring about the cessation of the undertaking which they had begun, saying: “Remember that on this day there died for us the Lord, who for the sake of our salvation did not fear to endure the cross, nails and the lance, punishments befitting criminals. But if your desire for a fight is so great, we, too, will stand ready after the coming day of the Lord’s resurrection.”

Men standing near the Emperor’s throne

But the Latins were so far from yielding to him that they closed their ranks and threw missiles in such profusion that they struck across the chest one of the men standing near the Emperor’s throne. At the sight of this, most of those who were standing near fell back, here and there, from the Emperor, while he, meanwhile, remained on his throne, not only without any sign of fear, but likewise reassuring them and chiding them greatly for their fear. All admired his presence of mind.

Finally, when he saw that the Latins, bereft of all shame, were invading the walls of the city and scorning his useful counsel, lie first summoned his son-in-law, Nicephorus, and commanded him to take with him the strongest men and those skilled in shooting arrows and go to the top of the wall. He advised him, at the same time, to hurl down weapons on the Latins as frequently as possible, but, for the most part, harmlessly, with bad aim, in order to frighten them, not to kill them. For, as was said above, the Emperor respected the religious significance of the day and did not wish to engage in civil war between Christians.

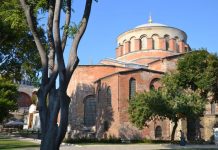

At the same time, he ordered some other chosen leaders (each with his cohorts, most of them provided with bows, but some armed with long lances) to charge forth suddenly from the gate which is close to St. Romanus, thus presenting the appearance of violence to the enemy. The battle line was so arranged that each spearman should march protected on each side bowmen armed with shields. Thus arrayed, they were ordered to advance against the enemy at a slow pace, and archers, instructed to turn about frequently here and there, were sent ahead to wound the Gauls at close quarters. Nmv, when the two lines were a slight distance apart, they were then to order those bownien who had spearmen at their side to use their bows carefully, aiming at the horses of the enemy, sparing the riders; and it was further ordered that the spearmen should charge with loose reins upon the Latins and with the full weight of their horses.