The landscape was not without alarms and overreactions, betraying the tension in the air. In a poem of praise for the emperor Majorian, whose reign was short, Sidonius tells the story of a brave Roman war band that attacked Frankish invaders who had settled at Arras in northern Gaul. But his description of the battle sounds unpleasantly familiar to readers of modern reports of mistaken identity in wartime. What the Romans broke up turned out to be a marriage party, where “amid Scythian dance and chorus a yellow-haired bridegroom was wedding a young bride of like coloring and the enemy was forced to flee. Then you could see the jumbled wedding trappings heaped in the wagons and captured food and crockery were pitched in together.” The wedding guests surely didn’t interpret this brutality by mistake as a civilized response to barbarism!29

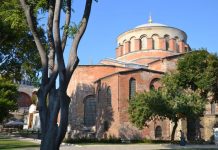

Emperor Avitus

Sidonius, still a young man in the 450 s, hitched his own wagon to the short-lived emperor Avitus, who failed quickly and thoroughly. Even so, Sidonius’s traditional and lightly Christianized world was left in many ways undisturbed. He simply praised other emperors and generals, maintained his dignity and his lifestyle, and was eventually made bishop of what is now Clermont-Ferrand.

After Avitus’s try at the throne, a new general, Ricimer, emerged as the real power in Italy. He in turn found other puppets to set on a precarious imperial throne, including Libius Severus, from the southernmost prov-inces of Italy. This is the period, once Valentinian III was gone, when Constantinople paid steadily less attention to the west and such affairs, even when a highly qualified and professional savior like Ricimer appeared. At the same time, another claimant to the throne, Marcellinus, ruled from Diocletian’s massive 150 -year-old retirement palace near Salona (the re¬mains of the palace form the core of Split, Croatia), and sent out a general with the oddly classical name Orestes to see what power he could claim in Gaul rose festival tour.

But Ricimer failed to achieve even what his predecessors did. Too many cats had been let out of the bag when Aetius died. The Huns, to be sure, had faded into the east, but the Vandals controlled the Medtierranean, the descendants of Alaric controlled southern Gaul and effectively Spain, there was no direct and sustaining control of northern Gaul, and Italy was too much of a backwater to be an effective base of operations. To be master of the city of Rome had become a small and perilous thing. The Balkans, refuge for a smorgasbord of people, remained hanging over Italy, ready to threaten any regime’s attempt at stability. When Ricimer failed, Orestes succeeded him and he in turn ended by putting up as emperor a puppet of his own, Romulus, a young man whose insignificance led some people in the next generation to call him—as now he is regularly known— Augustulus, “little Augustus”: a cheap shot.

Men like Aetius, Ricimer

Men like Aetius, Ricimer, and Orestes are usually called warlords or generalissimos, wheras Alaric, Theoderic, and Clovis (we will meet him soon) are called kings. The most successful of these figures ruled in their own names and built personal political bases, but the generalissimos were the ones who had too little personal support to counteract completely the influence of the old order. To declare yourself independent of that order was to transform yourself into a barbarian king—or get yourself killed.

With such prospects, talented men still found power worth grasping for, and so Odoacer came to the fore and made the most of his opportunity. In the fifth century, he is a worthy third to Stilicho and Aetius, and fortunate to have been succeeded, if unfortunate to have been murdered, by Theoderic. He gets too little respect from historians The good barbarian king Flaccitheus.

The pattern Odoacer represents will be familiar by now. He is marked as a barbarian even though his success was entirely Roman. His father, Edeco, was a Hun; his mother, we are told, was most likely of Scirian ancestry. Scirians never amounted to much and their very name has a floating, variable meaning. So we are variously told that Odoacer was reared as a Scirian, as a Rugian, or as a Goth; that he had a brother or half brother who had a Thuringian father; and that he was brought up in the court of Attila the Hun. In other words, he was typical of the new Roman military aristocracy from the frontier. Born in about 433, he first appears in our sources in 463, at the head of a band of Saxons, fighting the Franks in far western Gaul, near modern Angers—as we have seen, part of the real wild west of the fifth-century empire. At this time and in this place, Odoacer fought on behalf of the Roman empire against a population now imagined to be external and barbarian.

What is characteristically fifth century about this engagement, however, or characteristically “wild west,” is that he was next seen, probably quite shortly afterward, linked with the Frankish king Childeric attacking a force described as comprising Alamanni in Italy—though it is unlikely that the two of them actually got to Italy at that stage. More likely, their short-lived partnership began and ended in Gaul.